Register for free to receive our newsletter, and upgrade if you want to support our work.

Zagreb, Croatia’s capital, is home to a vibrant series of experimental music events, despite the obstacles that hinder the growth and development of its local scene. In the context of Zagreb, the term “underground experimental music” encompasses a wide range of styles: from sound art experiments, ambient and noise soundscapes to free jazz, riff-based assaults and adventurous dance music. Exploring the happenings that nurture these heterogeneous aesthetics thus becomes the best way to encapsulate and portray Zagreb’s scene: they gather communities and audiences and provide opportunities, platforms and networks for artists.

Within these past ten years, the landscape of the underground scene has visibly changed, not necessarily for the better or the worse. Many curators and organisers have moved on, taken long breaks, shifted locations and host organisations or transformed their activities in some way. Recalling Antonio Pošćić’s 2016 Global Ear article in The Wire about the Zagreb underground scene speaks to its instability. The main takeaway from Pošćić’s survey was that the scene was disparate, dissonant and, even then, undergoing a continuous transformation.

Today, 8 years later, very few of the mentioned events still function in the same format – or exist at all. Within the instability of the local context, events and projects often come and go. Despite several national and local cultural funding structures, the scene seems to still lack the financial and logistical resources to make participating in it a sustainable way to, at least partially, earn a living. On top of that, there is a continuous struggle to access Zagreb’s few remaining quality venues, since many spaces have closed down or still suffer the consequences of the 2020 earthquakes. While the current city administration has put into place an ambitious and commendable initiative to rebuild or repurpose several city-owned locations for cultural needs, this is still a long-term plan and doesn’t directly address the slow disappearance of grassroots venues.

Considering these conditions, this scene seems to be fueled purely by the passion of several collectives spearheaded by passionate individual curators. This fuel relies heavily on the intrinsic motivation and emotional resources of cultural workers. There is a certain shared madness there that inspires deep respect, but it needs to be balanced with the awareness that a healthy cultural ecosystem shouldn’t be expected to thrive solely on this resource. Through conversation with several of Zagreb organisers of experimental music events, I aim to explore what keeps them going despite the obstacles they face, and in a wider sense – what makes a scene sustainable?

Zagreb’s Experimental Music Initiatives

One of the most enduring efforts that has shaped the Zagreb experimental music scene resulted in a festival aptly named Gibanja (“Motions”). Gibanja is an experimental sound event that deals and promotes contemporary experimental music practices, with an additional focus on spatial sound.

Aside from supporting many local artists to create performances that use different modes of sound spatialization and showcasing many such international acts ranging from Thomas Ankersmit to Aho Ssan, some of the most impactful performances feature impressive audiovisual setups, carefully directed movement, the raw, intimate physicality of instruments or DIY machines, along with various apparatus and installations.

All of these formats support its mission of producing immersive experiences that alter the ways of listening and perception of sound and space. Some of the international artists that powered these experiences so far are Okkyung Lee, MAOTIK x Maarten Vos, Sylvain Darrifourcq, Ziúr & Elvin Brandhi, Kassel Jaeger & Eléonore Huisse, Kathy Hinde, Hugo Morales Murguia, Judith Hamann and many more. Founded in 2021, Gibanja marked the mutation of efforts by curator Davorka Begović, former artistic director of Izlog suvremenog zvuka (“Showroom of Contemporary Sound”), an important pillar of the experimental music scene in Zagreb presenting truly the most current and progressive sound explorations, inspiring loyalty and trust of the local audience.

It was partially imagined as a counterpart to Music Biennale Zagreb, a historically important institutional music festival which, contrary to its earlier years, lost some of its curatorial edge when presenting contemporary music. After 6 editions, Izlog ended abruptly in 2018 when the political turmoil and machinations of the management of the Student Centre, its host organisation and venue, resulted in the resignation of Izlog’s artistic director. Davorka’s programmatic mission soon found a new home in KONTEJNER, an NGO dealing with progressive contemporary intermedia art, with special emphasis on projects investigating the role and meaning of science, technology, and the body in society.

Other than Gibanja’s impeccable curation, it is its resources that make this festival and occasional one-of concerts a beacon of hope for the local independent experimental music scene: “Financing programs through various projects is definitely one of the main conditions necessary to make this happen. Within this, we should highlight the Creative Europe program along with other EU funding programs; the recent increase in cultural funding by the City of Zagreb, both by expanding program budgets and the institutional support of the City; and specialized foundations like Ernst von Siemens Musikstiftung.”

Because of the operational and financial framework of KONTEJNER, a well-established organisation with 20 years of experience, Davorka is able to receive monthly pay for her work, which unfortunately makes her an exception in the local landscape of experimental music. KONTEJNER, in addition to being a team of skilled cultural workers making these diverse funding opportunities possible, has recently opened its own venue. This eases some of the operational obstacles to maintaining a continuous program throughout the year but also introduces a new set of responsibilities and financial pressures, as Davorka explains.

Like many other cultural initiatives, Gibanja also uses the hospitality of grassroots venues like Močvara and a highly sought-after public venue available for free use to independent scene actors – Pogon Jedinstvo. Not too far removed from Gibanja’s inclinations, another noteworthy experimental music endeavor in Zagreb is occasional electronic music programs of the Multimedia Institute (MaMa), an NGO primarily dealing with critically engaged digital art, film, music and theory.

Curated by Petar Milat, these performances are produced in various Zagreb venues and often deeply rooted in collaboration with other organisers. Its curatorial approach was often a valuable addition to the late-night programs of Music Biennale Zagreb, bringing the likes of Vladislav Delay, Kim Cascone, Mikael Stavoestrand, Mouse on Mars, zeitkratzer, Christian Fennesz and many more.

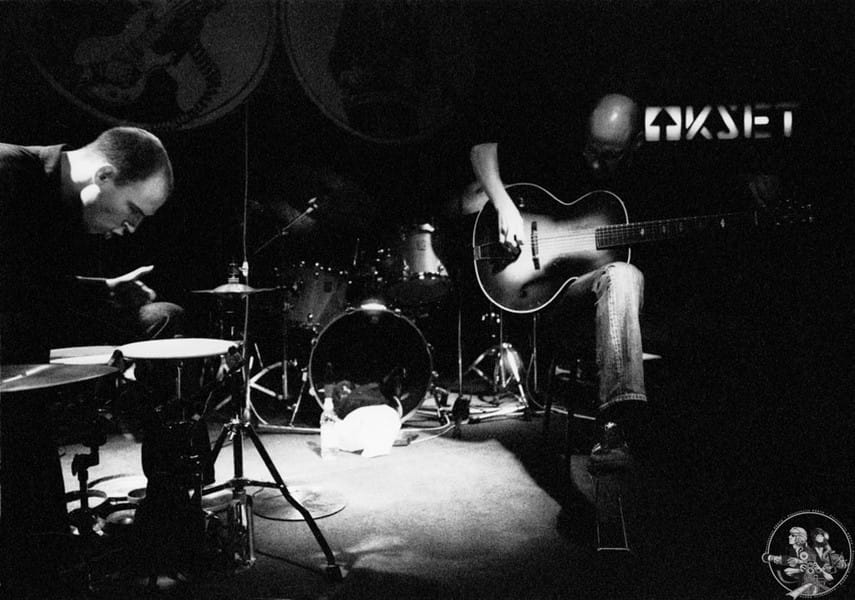

More unusual sounds that once echoed in the halls of the Student Centre came back to the cultural forefront this year. Another highlight of Zagreb’s experimental music scene, NO Jazz Festival, returned to enrich the capital’s cultural landscape with free and avant-garde jazz.

NO Jazz offered progressive jazz spinoffs and explorations at a critical time in the early 2000s, filling KSET, and later the Student Centre with the sounds of icons such as Peter Brötzmann, Ken Vandermark, Charles Gayle, Hamid Drake, Mats Gustafsson, Joe McPhee, Rob Mazurek, Chad Taylor, Matthew Shipp, Matana Roberts, Vijay Iyer, Otomo Yoshihide, Satoko Fujii, Dave Douglas, Bill Frisell, Mary Halvorson… It helped shape a generation of listeners, occasionally achieving packed concerts that would have, up until then, only been for the most radical and curious of ears.

It was founded by Mate Škugor, a then-student and member of KSET, the aforementioned student-volunteer run organisation and venue. Mate’s curatorial work through NO Jazz and its sister concert series Žedno Uho (“The Thirsty Ear”) left a lasting mark on Zagreb audiences. He describes his obsession: “To someone that has never been involved in this type of work, it is very hard to explain this inner urge that makes you do a job so uncommercial in nature, but it fulfills you in a way that money, and material values in general, will never be able to.” NO Jazz ended 15 years ago when it suddenly and without explanation didn’t receive funding from the City. Despite NO Jazz financing an above average percentage of its budget through ticket sales, it still very much depended on funding. As a result, Mate now emphasizes city and national funding institutions as “unreliable partners” and the biggest obstacles to the development of his projects in the past.

This situation initially led him to end NO Jazz Festival, and a similar fate awaited Žedno Uho later down the line: “I am one of those who insisted on (doing this job) until the very end, when I (financially) jeopardized my own family. That’s when I decided to make a radical change. I wanted to finally use my college diploma, which had been sitting unused for nearly 20 years, to find a job that would provide some existential security while still allowing me to pursue what I had lived for over the past 25 years.” For a time, there was no public trace of Škugor’s concert activity, until the news broke out about NO Jazz returning, bringin the likes of Rob Mazurek with local luminaries Roj Osa to an alternative club Vintage Industrial Bar and The Necks and David Murray / Ingebrigt Haker Flaten / Paal Nilssen-Loveand to Lauba, a gallery and event space of a more highbrow status.

Explaining his comeback, Škugor elaborates that it was made possible by “investing the money accumulated from the sales of his book “Music for thirsty ears”” and adds that, if necessary, he is now in a position to take out a loan to cover any possible deficit. Despite the real risks of such an endeavor with personal finances, he adamantly insists he has no intention of applying for funding from the Ministry of Culture and the City of Zagreb this time around. This rebellious path may not be feasible for most organisers, especially those up-and-coming and of a younger generation, but it illustrates one of the ways these conditions can create friction and frustration, even for the most persistent individuals.

To further delineate the experimental music initiatives that emerged from student spaces, in 2013, KSET gave birth to another project. ZEZ – Zavod za eksperimentalni zvuk (ZEZ is a playful acronym for “The Institute for Experimental Sound”) was founded by Ante Zvonimir Stamać as a biannual concert cycle, at first focusing primarily on avant-garde jazz and noise but over time spanning wider and wider across genres.

In 2018, the concert cycle mutated into ZEZ Festival, a yearly indoor event consisting of concerts and club nights, a sound art exhibition, workshops, lectures and discussion panels and an artist residency program. Throughout the years, it has hosted around 100 international and many local acts, including the likes of Colin Stetson, Lucrecia Dalt, Félicia Atkinson, Valentina Magaletti & João Pais, Matana Roberts, Peter Brötzmann/Heather Leigh, Blanck Mass, Sun Araw, IC3PEAK, Dälek, Duma, Shabazz Palaces, Gazelle Twin (realized in cooperation with Živa Muzika, another experimental music collective whose gradual disappearance from the scene left a lasting gap) and many more. However, because of the nature of KSET being a curious little student club, it was always a DIY, volunteer- based operation. Almost everyone involved—from the production team and tech crew to photographers, ticket sellers, coat check attendants, and venue cleaners—were KSET volunteers. Founded in 1969, KSET stands out as a unique example of a collaborative union shaped by its Yugoslav socialist context, remaining a breeding ground for a young idealists to this day. It consists of 9 sections for student members that gather around different interests (photo, video, audio, DJ, coding, technical skills, hiking, biking and acting), but share responsibilities and obligations that concern the club and the organisation as a whole.

Since it is a concert venue, it also serves as a training ground for young enthusiasts that want to learn to organise such events, while also providing a certain safety net for financial risks. ZEZ had the (unfortunately rare) privilege, as Unsound’s Matt Schulz put it, to do it “with someone else’s money”. Not having to invest personal finances helped its development, since ZEZ never could sustain itself on ticket sales alone. Even with the growth of its audience, it remained reliant on funding by local and national sources and by KSET itself, who invested funds through the years to cover ZEZ’s inevitable deficits. These, luckily, grew more rare and much smaller over time, but this was a result of a volunteer community believing that there are things that are worth “losing money” over. It is therefore not surprising that such adventurous programs came to life right there in KSET.

However, partially because of the nature of KSET’s membership, ZEZ organisers have a natural expiration date, many of us moving on with our lives after graduation. After Ante, I took over in 2015, balancing my studies with this newly-discovered passion for years. I stayed partially active in ZEZ even after I graduated and the artistic direction and production was taken over by Luka Babić and Matija Resman in 2021. Graduating doesn’t necessarily mean that a KSET member can no longer participate in the program. It is more about the personal limits of volunteering. Running such a festival or even just being a part of the team requires so much time, energy and dedication that once you enter the “real world”, it becomes exponentially harder to maintain it while seeking other sources of income to survive. Something’s got to give.

ZEZ is also currently in a transmutation era. After almost 50 years, its lair and home KSET got (allegedly temporarily) displaced from its space because of construction on surrounding buildings. This move has forced the fourth generation of ZEZ curators, Mirna Čupić, Patrik Klepić and Vid Marinović to find creative ways to organise this year’s edition in 4 different venues around the city. It seems that ZEZ being anchored in a youth association that has systems in place for passing on knowledge and experience makes it more resilient. Still, without the familiar infrastructure of KSET, volunteer work becomes more challenging – and it is still unclear what the future holds for ZEZ’s home base.

On the other hand, some venues have managed to remain unmoved in the face of challenges of navigating the local cultural landscape. Močvara (“Swamp”) is one of the most prolific alternative grassroots clubs in Zagreb when it comes to concerts that go against the grain. Nestled along the banks of the Sava River, this swamp creature has thrived for almost 25 years, supporting many influential concert programs—both those created in-house and those organised by external promoters.

Here we find Vrelo zvuka (“The Well of Sound”), firmly anchored by its collaborations with its host organisation. Vrelo zvuka presents world music in its contemporary and avantgarde forms. This concert cycle of curious folk hybrids is curated by its founder Emir Fulurija. Some of his notable international bookings within Vrelo zvuka include Canzoniere Grecanico Salentino, Monsieur Doumani, Yin Yin, Black Flower, Mdou Moctar, Stella Chiweshe, Nihiloxica, Senyawa, 75 Dollar Bill and many more. At the same time, it maintains its position as the most important program spotlighting local and regional world music projects. Vrelo zvuka has developed a steady, loyal and expressive audience circle.

Although the aesthetic leanings of this program are undeniably experimental in nature, Emir also underlines that “audience development is crucial for the sustainability of this story; it wouldn’t make sense to pursue these things if no one was engaging with them. While culture doesn’t need to depend on commercial profitability, it’s not practical to insist on things that, in some ways, no one is interested in.” Audience support is what motivates Emir to keep going. He began his journey in a student context when he created the long-running world music radio show Izvorišta on the airwaves of the alternative hub Radio Student. Like many others like him, he started it all for the love of this music and a need to express himself creatively. Initially, he didn’t expect it to be a paid activity, but over time, “it became important because volunteering only makes sense up to a point.” He goes on to emphasize the importance of at least a symbolic compensation for the effort he puts into making these concerts happen: “However, the income I receive from these events is so small that sometimes I feel it’s almost rude to mention it, but it’s important that it exists.”

Experienced in navigating these conditions, he remains optimistic when asked about his dreams for the future: “I believe anything is achievable, but everything has its place and time. One needs enough experience and knowledge to reach what might initially seem unreachable.” However, that doesn’t mean it is remotely easy. He quotes the lack of stability of institutional funding and a lack of venues in Zagreb as the biggest obstacles to this type of work in the local context. This is why Močvara’s support is crucial for many programs on the margins.

Another such program taking place at Močvara is ImproMondays, a series and festival of free improvised and experimental music that brings together local and international musicians to play in unexpected and playful combinations. It was founded in 2007 by Dragan Pajić Pajo, but after his passing, it was revived in 2018 in his honor by its current artistic director and organiser Damir Prica Kafka. Damir is another example of an individual whose passion serves as a cornerstone of the local improvised music scene. His mission has, luckily, also found support in this grassroots club.

At the same address where Močvara stands today, another cultural pillar of the Zagreb underground was born over 20 years ago. It later moved to a more central location in the abandoned Medika factory complex, becoming known as the Autonomous Cultural Centre Medika. With its exterior adorned in street art and interiors shaped by DIY construction, it stands as one of Zagreb’s counterculture landmarks, nurturing underground culture and grassroots activist politics. It is a home to numerous non-governmental organisations, galleries, studio spaces, music venues, a theater, a gym, and for a time, even a pizzeria. Although it is generally considered a squat, Medika pays monthly rent to the City, who owns this real-estate. Even after the damages from the 2020 earthquake and ongoing demands for these repairs to be implemented by the City, its most prolific music venue – Attack – still stands strong. It is there that something adventurous was allowed to flourish – an alternative club night named VOLTA.

In 2018, three enthusiasts—Josip Kornet, Nikola Krgović, and Ivan Oberan, later joined by Mislav Matić—began hosting club nights that pushed the limitations of genre. These nights gradually cultivated an audience of dance enthusiasts eager to be surprised and challenged on the dancefloor.

According to co-founder Josip Kornet, “Every VOLTA event receives feedback, both negative and positive. Over the past two to three years, we’ve managed to create a microscene around us—people who share our obsession with weird music. This includes audience members we can engage with, as well as other organisers and DJs we frequently collaborate with.”

Throughout the years they have brought object blue, LCY, Lee Gamble, Slikback, ABADIR and CCL to Zagreb, as well as supported most local and regional electronic live acts and DJs that experiment within this field. They also hosted the first official Croatian Boiler Room event in 2021. While supported by Attack and its dedicated crew, they have few other resources to keep it going. It has always been an out-of-pocket operation; even if a booking covered its costs and turned a profit, the money went right back into funding the next gig. This limits them to do foreign bookings once a year, while spreading out less financially risky local lineups throughout the year: “…sometimes even a full club isn’t enough to cover all production (costs). Producing smaller events and local lineups is fulfilling, but the fact is, problems arise when we want to achieve our dreams of bringing more expensive and impactful names from the global scene.”

This instability inevitably creates a certain burnout, as one of VOLTA’s head honchos admits while describing his deep emotional investment in each event he is a part of. Within the same space, Kornet recently started a new program with producer Kristian Bagarić (varboska) and visual artist Monika Milas, often in charge of creating club scenography for VOLTA parties. This new phenomenon called SNOP (“BEAM”) is an immersive ambient alternative to the typical club or concert experience.

Otherworldly dark yet ethereal sculptures crafted by visual artist Monika Milas fill the room, their twists and turns encouraging the audience to lie on the ground or sit against the walls, watching the light and projections dance across the surfaces. Its visual and sensory qualities are inextricably linked to its core concept.

They present live electronic music, DJ sets and occasional acoustic performances. One of its co-founders, Kristian Bagarić elaborates that SNOP aims for “relatively improvised, automatic description of complex emotions (through music) with a purpose of therapeutic catharsis, while enriching the transformed space that allows and eases the audience into an experience of deep introspection, relaxation and vulnerability around their close friends as well as more distant acquaintances.” What’s intriguing about this event is that, despite having only three iterations, each one has attracted an impressive number of people—primarily from the younger generation—who are able to sit on the floor for hours, listening closely with full attention and dedication.

Again, what comes up as their motivation, aside from the pure passion for this type of experience and the sense of collaboration with like-minded people, is the effect it has on the listeners: “Nothing else quite fulfills me in that way and leaves me content for days—even weeks—after the event, especially when I see how relaxed and happy people are from the unique experience of that evening.” So far, SNOP doesn’t rely on funding or ticket sales – entry is free of charge. For Kristian, music events are not a source of income. Moreover, he feels that expecting such music events to be a primary source of income is a trap that undermines the quality and authenticity of the experience. He works an unrelated job, which, by his accord, leaves him free to do what he loves without the expectations or pressures of financial success or sustainability. On the other hand, he balances this statement with the understanding that the lack of financial structure ultimately results in less time and energy to sustain these volunteer-based activities.

It is hard to discuss sustainability with a straight face without underlining that this string of passionate individuals have spearheaded adventurous programs for years or even decades without their working conditions ever significantly improving. Almost none of these organisers make a living, even partially, from their activities, sometimes finding themselves in a state of ongoing burnout due to the precarity and unpredictability of the work that gives them purpose. This, to some extent, is also the state of a big part of the Croatian cultural sector. When speaking about the obstacles to the development of the experimental music scene, Davorka emphasizes the underpayment of cultural workers: “Because of this, there is a lack of workers in the sector, which causes burnout for many of us.

All of us get into this type of work primarily because of a tremendous passion and no one is active on this scene because of the money, but that automatically decreases the chances of new kids joining us in the future.” This sentiment echoes my personal reflections on the cognitive dissonance between the idealism that keeps these curators going for years and the reality of unpaid or barely paid cultural work. The perceived purity of these unpaid endeavors easily pander to idealistic visions of the world for those of us involved in these projects. However, the reality of working conditions often force them to stop. When the internal fuel is depleted, what is left to sustain up-and-coming organisers?

After being active on the scene for 19 years, Davorka looks at the scene aware of the passage of time, describing her dream of creating a stable structure for future generations: “The festivals and projects we work on make up the scene at the moment, but they come and go, as do we. And all of us are getting older. That’s why I think that working conditions for new generations are the key to the future of the experimental scene. And I don’t mean only financial conditions.” The thing is, these marginal musical expressions will probably always depend on a shared passion, and most certainly, on institutional funding.

Experimental music is essentially non-profitable – this art form, like many others, primarily belongs to the domain of the non-profit cultural sector for a reason. This sector is the result of a societal agreement that there are things that shouldn’t have to rely solely on the ebbs and flows of a market economy. In this sense, there is never enough available funding and continuous effort should be put into creating more opportunities for cultural financing. However, compared to the rest of Croatia, Zagreb projects are doing well and the scene seems to be developing, partially thanks to the budget a capital city wields and the amount of audience it can provide as the most populated city in Croatia. Besides a couple of admirable exceptions (Drugo More in Rijeka, Audio Art in Pula and Ispod Bine in Split), there is not much else happening in this area in other parts of the country. And while finances, both institutional and those stemming from audience support, are vital, they are far from being the main thing to sustain this type of artistic expression.

Most interviewed organisers seem to be somewhat content with having this pursuit as a hobby. And there is no mandate for professionalization – doing this type of work as a hobby is probably the most common way of doing it and the Zagreb scene (and many others like it) is sustained through the work of such individuals. But the fact is, without collectives to pass on their experience and knowledge, these programs end when the internal fuel of the curator depletes. The alternative to this is for organisers to be a part of at least partially formalized initiatives and organisations that pool resources and allow for a division of labor focused towards professional work in the non-profit sector. What can be set up to get willing individuals from the first to the second option, would need to involve accessible ways of informal education, a sharing of information, continuous logistical support and the creation of stable networks that foster collaboration. All of these programs already survive because these (mostly) individual efforts are supported by non-profit organisations and the values they aim to represent. They are sustained through community.

Davorka offers her hopeful vision for the future: “I think we need to – and I hope we will succeed in this – “build” key places that will be a stronghold for future musicians, sound researchers, curators of experimental sounds; where they can have a serious curatorial and production support, where they can get advice and information; where they can have financial, technical and operational help; a stronghold that the youth will be able to rely on.”

Supportive environments can empower future generations – be it through the power of community mentorship, support and connection or formalized organisational structures. By fostering collaboration and establishing resources, it is possible to cultivate a more thriving community where the next wave of artists and curators can flourish with less uncertainty. Sustainability is created through collective action.

-

This article is brought to you by Easterndaze as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.