Register for free to receive our newsletter, and upgrade if you want to support our work.

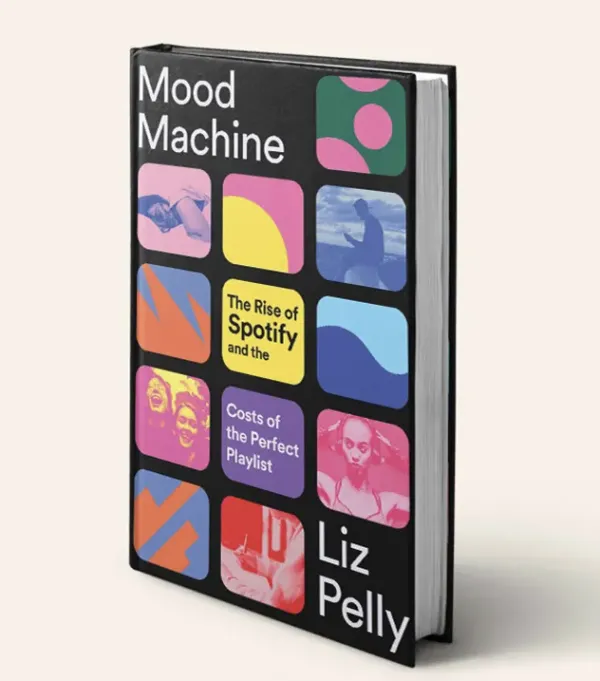

Their performance was built on songs by Slovak vocalist and composer Adela Mede, who combines in her lyrics the three languages she grew up with – Slovak, Hungarian (her parents’ mother tongue) and English. She was joined by an artist whose work she has long admired, Swedish composer and sound artist Marta Forsberg, who accompanied Mede’s songs with violin, electronics and voice, and donated one of her very own songs for the finale. Nindya Nareswari, an Indonesian light designer, now based in Berlin (like Forsberg), transformed the Kuppelhalle through an interplay of light, fog and large sheets of reflective foil.

With Verena Hahn, they talked about folk music, cultural identity, collective singing and finding the right place to live and work.

Verena Hahn: Let’s start at the beginning of this collaboration. What was the first thing you did? Where did you start?

Marta Forsberg: With Adela’s music.

Adela Mede: I guess so. We knew we had limited time, so I decided to just do what I usually do and somehow make it better. I recorded myself, they could listen through, and then Nindya came up with the light dramaturgy. It was a continuation of what you’re interested in, right? Like with the reflections?

Nindya Nareswari: Yeah. I enjoyed exploring the music and quickly got a picture in my head of what kind of mood or scene it suggests. I think of your music as a movie. I also checked one of your video clips. And from there, my imagination developed, like, okay, I can see the fog…

VH: How do you imagine it? Do you think of existing places, like a forest or underwater, or is it more abstract?

NN: I think of light in terms of time, like the light in the very early morning, for example. With the first song, I imagined it was dawn and time was passing. With some other songs, I had some difficulties understanding what they were about. That’s why I asked for the lyrics and translations. And sometimes I also wanted to know if it was a new song. I need this kind of information to visualise it. But everything I did was an interpretation of my experience with the music.

VH: What was your entry point, Marta?

MF: I was most excited to perform someone else’s music, having this supporting role of going in and trying to understand what this sound world is. How can I step into it with what I have, maybe adding something but not making it different than it is? Finding this balance is so much fun. And I do it too little. I could totally be part of someone’s band and play their songs.

And then I was just very open to learning her songs. I felt like, oh, I’m just going to bathe in this universe. I found the role of language in her music very interesting, and I was reflecting on that, thinking how I relate to that in my own music.

VH: Both of you are interested in choirs and singing together. One of Adela’s songs is called “Sing with me”, and one of Marta’s songs is called “Singing for each other”. What is it about collective singing that’s interesting for you?

MF: I definitely don’t identify as a singer. But I’ve always sung in choirs. Collective singing has always been a part of my daily bread since I was small, but never as a single voice. When I sang in my own tracks, I just needed a voice. It’s easier to sing myself than pay someone to come and do it. I’m starting to explore now and have discovered that I can also use my own voice as an instrument. And before that, I was mainly just super fascinated by other people’s voices.

AM: I’ve been writing my bachelor thesis about Marta’s piece “Light Colours In Jyderup”. In 2017, Marta did a residency in Jyderup, a village in Denmark. She had lots of violin sketches recorded. As she was working right next to a music school, she invited some of the students to just explore with her. But Danish and Swedish are very different languages, so Marta and the students couldn’t really communicate. Then Marta asked the students to imitate the violin sketches. And that’s how this piece evolved.

This idea of working with students was so inspiring to me. When I came back to Slovakia, I wanted to get myself to this point where I could work with people who aren’t going to sing super perfect. So I slowly worked my way. I did a project with students as well, actually inspired by Marta, with my friend Tomáš Urík. We did a site-specific vocal performance called “Prestávka” for a school in Považská Bystrica that some of them went to. And now I teach a choir of young mothers.

I’m just so inspired by the voice and how people relate to it when they haven’t sung for a long time. I’m learning so much about it. It has such power.

VH: You create choirs artificially by looping single voices, but you also work with actual choirs. When do you decide for one and when for the other?

MF: I like a dialogue happening in the music between different voices. For some years, I’ve been into the synthesised singing voice. It sounds so robotic and so amazing. This quality combined with the human voice – I find that wonderful. So having different voices is engaging for me when I compose.

But then I’ve also got feedback, like, “why do you use all these other people’s voices? Why can’t you just sing yourself? It’s enough.” I think I feel this sort of hesitation to put myself in the centre, because I’m not used to using my own voice. This is what I’m exploring now.

AM: When I was at university, I was really shy and I’d make songs with reverb and delay, hiding my voice. And then my lecturers were, like, “what are you doing? Just try using dry voice and see what happens.” So on my first album, I made very sure to use as much dry vocals as possible. To get to know myself and my voice.

VH: Adela, I don’t know if you consider yourself a folk artist, but I find your digital exploration of voice interesting. Folk music was always bound up with a certain place and growing within certain restrictions. Being able to loop your own voice also frees you from being in one place or being with one community. What’s exciting for you about the combination of digital and non-digital practices and technologies?

AM: Folk music is really important to me. It felt like a language I could relate to my parents as it was so important for them for a long time. I think it’s still important for them, but not the way it’s practised in Eastern Europe at the moment. Folk music became a language we could speak together. But it feels like they’ve moved on, and now I’m, like, “but you know, you liked this some time ago.”

One of the most important lessons I learned through my academic studies is not to culturally appropriate, even though it might be my own culture. But how do I explore my attraction to folklore in a way that isn’t like, oh, I want to make it mine now? In my music, the way I try to approach it is that I look for narratives in folk music that can be used to navigate the present.

MF: It’s interesting that you didn’t want to make it your own or appropriate these songs. In Swedish folk music, the tradition is to pass on these songs.

AM: I went to an English school my whole life, so I was in a very different bubble than my parents. I didn’t have this upbringing about folk music and how it’s about passing traditions down. Culturally, I was very much westernised by going to an international school and studying in London. Now I’m slowly making my way back. I’m trying to find friends who speak Hungarian so I can practice the language. It’s like returning home.

MF: It’s very interesting. This brings up so many questions, like, who owns this music and who has the right to perform it. And the idea that someone has the right more than someone else, which is cultural appropriation. It’s so important to think about it, to not overstep or be clumsy about it. But you grew up in these countries and still…

VH: I think what you’re doing is something very much your own. You’re referencing folk themes, but your music is also about migration and globalisation. It reflects a most contemporary state of being between cultures.

Actually, in all of your biographies, migration plays a big role. Did moving change your perspective on where you come from? Geographically, culturally, but also artistically?

NN: I’m from Indonesia and I came to Europe for my master’s at 21. I also went to an English conversation class. Everyone was from different parts of the world. So it felt like I had to represent my country in a way. But I didn’t want to; I’m a citizen of the world. I just want to represent myself.

But people consider me to be racially different. Like, where are you from? Because I look very Asian. So what should I do then? In terms of light art in Indonesia, we have Wayang, the famous shadow puppet theatre. But I don’t want to do this because it feels too easy to present myself to others in this way. I just want my work to be universal in a way.

Maybe it’s a kind of denial that I’m from Indonesia. But you can also interpret it as exoticism. Until now, I still try to figure myself out, like, should I do something a bit more Indonesian? For sure, there’s something interesting about light to explore in Indonesia. But I just want people to see me as I am, not through my Indonesian nationality.

MF: That’s interesting. I grew up in Sweden with a Polish mother and a Swedish father. So I had this very classic thing of being half, half. You’re not completely Swedish, but you’re not Polish either. In Sweden, I pass as half, half, and in Poland, I pass as Swedish. And in Germany, I pass as Polish because when I speak German, I have a Polish accent, which is strange. There’s this in-between-ship all the time.

While making music, of course this is something that comes up, but I never really wanted to own it either. I also didn’t know what I’d say with that. How interesting is it? Isn’t it already there? Whatever I do, it will always be there because it’s me. And music is such an abstract art form. When I listen to music, it’s all about feeling into this music and enjoying it from my perspective.

AM: Obviously, it’s nice to be part of a community as an Eastern European looking for identity. But I realised while you were speaking that it’s just a small part of the puzzle. For me, the most important thing was that I moved to London and my parents didn’t understand that. It’s more about this pain or lack of communication. And it was all about just me trying to find a way.

VH: The music industry is very much focused on Western or English-speaking music. Do you feel free to do whatever you want artistically, or do you have the feeling you have to cater to Western interests? Is it, for example, easy for you to work from Bratislava, and not from Berlin or London? Or to sing in Slovak and Hungarian, and not primarily in English?

AM: For me, language is the whole point of it. I never felt the pressure to make music in English.

And you know what? It’s also kind of like my rebellion against this.

Having lived in London, I know the reality there. It’s a tough place to live. One of the reasons why my husband and I left was because he couldn’t find a job. And I just finished university and my income would just be swallowed by rent. I had spent most of my youth in London, where I had friendships and contacts from my university. Moving back to Slovakia, I had to start over. It was really hard. Now it’s been four years and I’m slowly feeling like I’m back.

MF: For me, moving from Stockholm to Berlin was kind of a pragmatic choice. Many people thought that I moved here because of the great scene and I was, like, no, it’s because my partner doesn’t want to live in Stockholm and he’s German. Now I’m starting to enjoy precisely the fact that there’s so much music. The club scene is incredible. I’m starting to accept that I’m here and that I can also enjoy the city for what it is, not trying to push that away. Because it became so much pressure. This idea of moving to Berlin, to the big city, coming from Stockholm, where Berlin is always like the Holy Grail – like, we wish we were like Berlin, but we’re also happy we’re not. We’d like to be. But we’re also happy that we’re much tidier here. It’s like this weird little sister thing. All my friends were quietly disappointed that I moved to Berlin, “the better city”. And I was, like, it could have been Hannover, but it just happened to be like this because Andreas, my partner, likes to live here!

VH: Do you have the feeling that you can do the work you want to do, or do you feel like you have to adapt to certain expectations?

MF: I come from a really ambitious group of musicians that I was working and studying with in Stockholm. It was very cliquey. It’s a small scene and the standards are tough. Moving to Berlin, it was just, like, anyone was doing anything here. You can be part of this or that scene, and no one will judge you. You can do whatever you want.

That was different from Stockholm. Stockholm is a business city and very much connected to the pop music industry, which is huge there. That business-minded mentality is leaking down to all other genres as well. It’s very hard to work DIY, just try things out and experiment because you always have to have a very clear vision of what you’re doing. It has to be sold. Coming here, it just became more punk.

VH: How is it for you in Bratislava, Adela? Can you make a living as an artist there?

AM: Up until now, funding has been pretty good. But neither I nor my husband work exclusively within Slovakia because it’s not possible. I can’t gig just around Slovakia, but I go to the Czech Republic and Poland a lot. Now I’m part of the SHAPE platform, so that’s opening more doors.

Life in Bratislava is becoming harder, economically speaking. But I have no intention of leaving home anytime soon. Having been to London, I feel like there’s so much more I can contribute here. It feels like the right place to be. And, you know, I get so homesick. A lot of my work is about home. Even now, I’ve been in Berlin for 12 days, but I already want to be back home with my neighbours. I need to process what happened here in my reality, so that I don’t forget my reality. I went to this British school and I didn’t know what was going on around me. And I just never want to do that again.

MF: Wow.

AM: It was my parents’ choice to send me to such a school. They wanted me to be more open to the world because they grew up in a different kind of world. And, at the same time, they regretted it. I just don’t want my parents to feel so disconnected from me again.

VH: How is it for you to perform music in front of audiences that don’t understand the lyrics? Is it important for you to be understood?

AM: Initially, singing Hungarian in Slovakia was a bit of a shock to the system. I have songs where I rhyme Slovak with Hungarian. When I started playing gigs around Slovakia, I could hear the audience making comments, like, what’s going on? But now people know me a bit more, so they know what to expect.

It was also nice to hide behind Hungarian initially. The song “Holnap” is just, like, “... yellow leaf, yellow apricot.” It’s just so random. My mum was, like, “what are you even singing about? It’s so abstract!”

In Slovakia, we have this very natural behaviour to imitate Western cultures. Especially in music. I think it’s time to confront the question of why we feel the need to sing in English. It’s not that we should only sing in Slovak, but just to reflect on the reasons behind our choice of language. If singing in English feels more natural to you, why is that?

VH: In Germany, folk culture is something we’re really cautious about. It’s obvious because Germany wasn’t colonised, but was a coloniser. Here, folk culture has often been instrumentalised to define what a people is or what’s natural. Is folk culture alive in your country?

NN: In Indonesia, we have a lot of provinces and a lot of islands, so we speak many different languages. For example, I’m from West Java, so I learned Sundanese and traditional music from West Java.

Since Indonesia’s independence in 1945, we officially speak our national language, the Indonesian language, or Bahasa Indonesia, as well call it. This language is rooted in Malay and was adapted from different languages such as Sanskrit during the Hindu and Buddhist Kingdoms era in Indonesia, Chinese due to the spice trade, and Arabic owing to the spread of Islam. The colonisers – like the Dutch and the Portuguese – also left their mark, so everything is mixed together. There are people in Indonesia who still don’t speak Indonesian. So sometimes there are misunderstandings.

The younger people try to speak English because they want to be more modern. I think in Indonesia they want to be out in the world because the country is often seen as a third world nation. That’s why we try to speak English very fluently, I guess. And that’s why for me it’s very interesting to learn about traditional music again.

MF: Do you feel a general interest in wanting to learn about traditional music and art among friends of yours?

NN: I think so. Also at CTM, there were lots of Indonesians exploring that, in terms of sound or instruments. The band Kuntari, for example.

MF: They were so good! It was crazy.

NN: Tesla, the guitarist, is actually an experimental jazz musician. But now he’s exploring traditional music as well. And there was a workshop by my friend Bilawa Respati, who is into gamelan and experimenting with it digitally as well. Many artists from this generation are exploring the traditional and modern together.

MF: Moving to Germany, I found it interesting how problematic the German relationship with folk culture is. In Sweden, it’s very intertwined with everyday life. You learn to play these songs in school. I have many friends working with folk music as their core expression, a core source of inspiration for their music-making. So it’s just something I grew up with, but it’s being torn in different ways in this new political climate of Europe. It’s not as neutral as it was maybe 20 years ago.

VH: Last question to sum up: is there something you’re looking forward to? What’s coming next for you?

NN: I have unfinished business with some materials that I can’t use in the festival. I’d like to focus on the material for now to make a light installation, and I want to explore more. Plus I’m looking for residencies.

MF: My next step is a project with two dancers. I’ve been doing music for choreographers and dancers before a lot, and now I’m switching the roles. I got funding to make a dance performance. I’m basically getting background dancers for my random experimental music (laughs).

AM: I have SHAPE residencies coming up in Prague and Bucharest. And I’m going to record two albums. One with my own music, and one album of folk song covers. It’s about the expression of love. So a busy year. Usually, the more I work, the more prone I am to getting sick. So I hope this pattern doesn’t continue.

MF: You have to work less, basically, to be less sick, huh?

AM: I don’t know if that’s possible. Maybe less stress. But I’m pretty sure I’m going to get sick when I get home.

MF: Really? Do you think so?

AM: I think this was so stressful for me, the CTM. (Laughs) My body’s just going to disintegrate. So I’m looking forward to being in bed.

Photography: Udo Siegfriedt / CTM 2025

This article is brought to you by 3/4.sk as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are, however, those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union (EU) or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the EU nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.