Register for free to receive our newsletter, and upgrade if you want to support our work.

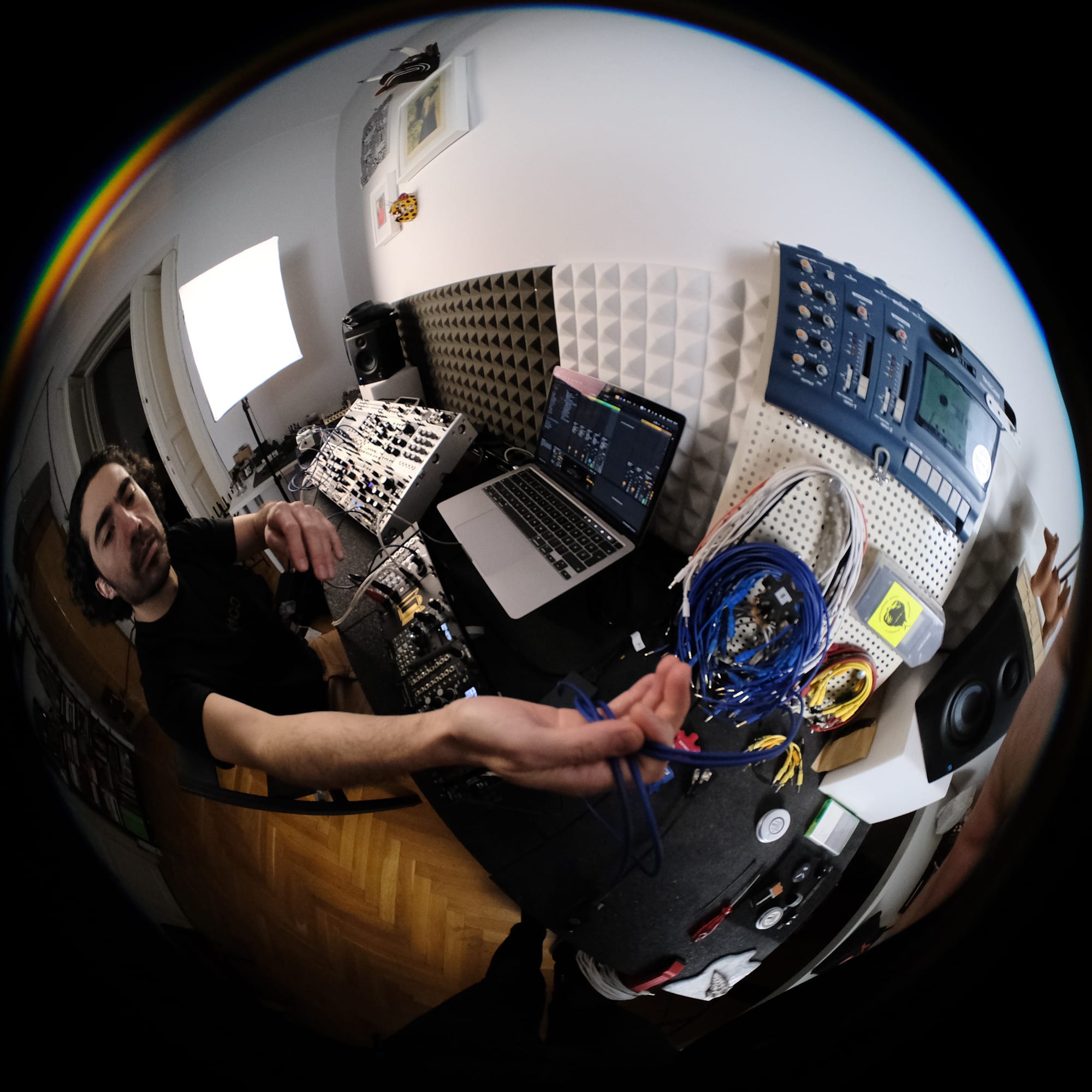

Esteban de la Torre is a musician and cross-disciplinary media and sound artist. Deriving from his background in visual arts, animation and sound design, his work spans from large scale art installations through multichannel spatial sound spaces and audio-visual performances, to soft circuitry for embedded electronics on experimental interfaces. He is a co-founder of the renowned EJTECH Studio. His work has been presented at numerous art galleries, museums and festivals such as the European Media Arts Festival (DE), the Smithsonian Hirshhorn Museum (US), the Design Museum Holon (IL), LOM Space (SK) and the Ludwig Museum (HU). He has also had commissions for feature films and commercial brands including Dune: Part Two, Blade Runner 2049, and DIOR. (x)

I met Esteban in his studio on a November afternoon to ask about his practices, current and future projects, and what drives him as an ever-exploring artist with his main focus on sound.

When did you first get in touch with making music?

When I was really young, maybe in third grade, I really liked recording stuff from the radio to tapes, like we all did. I had a cassette recorder and a radio, and when something came on that I liked, I hit record. Also, my mother plays the guitar, and I quite often took her acoustic guitar just to jam on it. I also asked her to teach me something, which she did, but you know, that was more like some Simon & Garfunkel-kinda stuff, or like Julie Andrews, Cat Stevens, etc. Eventually, I asked for an electric guitar, and then I started a band with some of my friends. We played some nu-metal shit [laughs]. You know, with a detuned D and heavy distortion. This was all happening back in my hometown, Mexico City.

At what point did you turn to electronic music?

The first time I started to respect electronic music was the time I first arrived here in Budapest. Before that, I was mainly into hardcore and aggressive metal sounds, and all electronic music I had heard up to that time was pretty much pop, or it wasn’t “true” enough for me. I was not exposed to proper electronic music in Mexico–only here in Europe did I first hear drum and bass. I moved to Hungary in 2000, and that was a starting point for me, that’s when I started listening to proper electronic music.

I respected drum and bass, and as I saw the scene around it, it was so cool and so interesting. I really saw the movement and motion in it, pushing sounds forward, and I really loved it.

I did not have any gear at that point, so I did not make drum and bass, but I made mixtapes–and I wasn't even properly crossfading the tracks, I just simply put one track after another. Later on, me and my friends figured out how to mix with two Winamps, and then we did mixes like that. We didn’t even do this because we wanted to be DJs, we just liked to listen to these mixes–I walked around with my walkman in the city, and this was what I was listening to, so I did these for myself.

What were your first steps in electronic music making besides making mixtapes?

Drum and bass opened up a lot of doors to me: after that, I also became interested in graffiti and hip-hop. Getting more involved in hip-hop culture, I was very much into scratching too, so as something that is electronic music-related, this was one of my first attempts at doing something. Scratching, mixing, but not as DJs would do it, but more as something we know as turntablism.

Later on I got more into electronic music making. My first hardware instrument was the Roland SP-555 sampler. I was really interested in this super drugged-out footwork stuff that is totally distorted. And then, of course, there were the Brainfeeder / SkullDisco / DMZ times, which had a huge influence on me too. Still, I was very shy at that time. I had friends who did make music properly, and of course they let me use their stuff too when I asked them, but I never had the confidence to actually say that ‘I want to be heard’ or ‘This is my voice’.

I was studying animation at MOME, and I did the music for my animations. Slowly I realized how much I enjoy making music, and I started to take it more seriously. At that time I was also making interactive animations and projection-mapping. I got to join a crew called Bounce who were making parties in Fogasház, and I was doing the visuals for those. For all those sound-reactive visuals, you needed to know a bit of computer-programming, so I delved into that too. And so, all this interactive-projection mapping and learning how to do it, led me to Max/MSP (a modular visual programming language for music and multimedia–ed.). Max/MSP was the first thing where I said, ‘oh fuck, this is infinite, this is so cool’. I felt that this could be a tool that I can both master and enjoy using at the same time. And this [he’s pointing at his Eurorack modular system] is really just a physical manifestation of Max.

Up until the pandemic, even though I had a couple of gadgets like the above-mentioned sampler or the Organelle, I was mostly a Max person. During the pandemic a friend of mine got stuck in Germany and asked me to go to his apartment in Budapest to pick up his Eurorack system, because he knew that he was not gonna be able to get back to Budapest in the next couple of months, and he didn’t want anything to happen to his system. So I went to his apartment, picked up his system, brought it here, and… then I was bored, so I opened it up and started playing with it [laughs].

And I guess, since you were already familiar with music-making concepts and a modular approach to do things, you could figure out quite quickly, how you can use the Eurorack system?

That’s right. In Max, you know, because it is so infinite, it can easily give a feeling of vertigo; it is a bit intimidating. For example, if you have an idea for a reverb effect and you want to create it in Max, it can take a lot of hassle until you can properly adjust everything to get that reverb, then you can make 1000 instances of it and chain them one after the other. But if you are working with a Eurorack system, then you just have a whatever reverb, and that’s it, you have to make use of that. Limitations like this are so liberating.

During those times in the pandemic, while I was here in my studio, I got so much into Eurorack that slowly I started to build my own system. With this, I think I really found my workflow, I feel so comfortable using this instrument. Before that, every time when I had an opportunity to play live, it felt for me that it was a kind of performance, in the sense that I was putting on a ‘play’ of something that I wanted to show. But with Eurorack, I really think that I can show something I feel, and something I want to share. It feels much more honest, comfortable, and natural.

Let’s talk a bit about EJTECH, the project you run with Judit Eszter Kárpáti. To quote your own statement, ‘EJTECH is a polydisciplinary artist duo working with hyperphysical interfaces, programmable matter, and augmented textiles as media to investigate sensorial and conceptual relationships between subject and object, aiming to rediscover networks of emerging structures and immanent causality within realist metamaterialism.’ What are the main driving forces behind EJTECH?

The idea of creating tools to explore sentient materialism, (call it panpsychism, pantheism or thinking of consciousness as a fundamental element in the universe) is core to our aims as EJTECH. By inciting matter into motion or creating augmented materials we intend to itch and blur that boundary between the subject and the object. Where do you end and the other begins? What are the boundaries of self? Your skin? Your clothes? Your thermal print? Your memories extended into an iPhone?

I’m a big fan of traditional artworks, I love paintings and sculptures, but the idea of having a finalized painting hanging somewhere… this somehow feels like dead media to me. As it’s in its final, solid state, something that does not go anywhere. When making artworks, I always struggled with how to overcome this, so mostly I always made smaller systems or interactive works. And these were always on the boundary of interactive art and fine art.

What has changed over the years?

I think the overall common denominator between Judit and me is still the same. I think we are more focused now. Ten years ago, when we started out, we were mainly exploring what we can do, and now that we feel more comfortable with the tools we have, we know better what we want to do. Our manifesto from ten years ago was very abstract and playful, and now it is much more condensed and has more dedication.

When we are talking about EJTECH works, are you ‘just’ working on the sound side of things, or are you also involved in the other aspects, like dimensional or textile questions?

Of course, over the years I’ve become much more familiar with different mediums, whether it is textile or sculpture, or things that are normally not part of my practice. I mostly focus on the sound, our electronics, and our graphics, while Judit focuses mainly on the material side. So we do have our roles, but at the same time, we also overlap in practice during the production of the artwork. Textile and electronic music have many common traits such as rhythm, pattern, texture and so on, so by the get go we already have common pillars to build a concept from.

When you’re working on a piece, at what stage of the process does the sound part come in? Are your pieces always sound-related?

Yes, almost everything we do includes sound. Sometimes it’s in the forefront, sometimes it's just in the background. When does it come in? It’s hard to tell, because it is very project-specific, plus my approach to involve sound-matter can also change while we are working on a project.

With EJTECH, what we are trying to do in the end, is to create a tool that can be used by visitors. As the greats like Richard Serra or James Turrell have done. Turrell, for instance, creates these Celestial Vaults as a tool to gaze at the sky. With his Roden Crater, he is transforming the inner cone of the volcanic crater, which in turn can be used by visitors to view and experience sky-light, solar, and celestial phenomena. We are very much inspired by artworks like this that create large-scale tools.

What tools do you use?

I love Bela, which is a microcontroller that can run Pure Data and SuperCollider patches. What I like about it is that it is specifically made for audio, and when we have a gallery or museum situation, the museum or gallery staff can easily turn it on or off, it never has any issues. Nowadays we can run Max too on a Raspberry Pi with RNBO, but this is something that came out like a year ago, so it’s still pretty fresh.

In July 2022, you did a piece called ‘Formalized Music for 4 Winds’ for the Dome of Magyar Zene Háza, which was an audio-visual piece created specifically for the 31 speakers of the Dome. Can you tell me a bit about this work and how it came to fruition?

It was inspired by my love for Xenakis. One of his pieces is called ‘Terretektorh’: one of the main ideas behind that work is that it is written for 88 musicians, who are scattered around the audience. So, depending on where you are standing while the musicians are performing, you might get quite different experiences from that piece.

So I knew about Xenakis from my earlier research, and when Magyar Zene Háza reached out to me with the idea of creating something for their space, I was very happy to take part in it. I think Xenakis was also very much interested in how chance and randomness play a part in music, as well as the physicality of sound. Similarly to this mindset, I also tried to explore what it could mean for the listeners to be in a multi-channel space and how chance can play a part in that.

I was in that really lucky position that I could actually compose that piece in the Dome. I had about a week, and every day, once Magyar Zene Háza got closed for that day, I went down to the Dome for the night and jammed, composed, and tried out some ideas. This tight creative process couldn't have been possible without all the assistance and technical knowhow from ambisonics, spat genius Zétény Nagy.

Let’s talk about EccotVirgo, your solo outlet for sound and music. How would you describe this project?

Within EJTECH, we have several intellectual grid system builds, making a rather mathematical-sound art kind of thing which, at the end of the day, is intended to bypass your mind and reach deeper. This is rather manifested as material artwork, not as dance music at all. And with EccotVirgo, what I like to do is this very free-form stuff with broken beats, dub, and drone. It is a place where I can ventilate my love for all of this.

I am very much into early dubstep, Skull Disco, and everything Shackleton was doing. At the same time, I’m also really into drone, like Earth 2, Sunn O))) , or King Tubby, Scientist, Basic Channel, etc. So yeah, with this solo project I just do what I like, with no compromise, no consequence.

As I was preparing for our talk and tried to look you up, I could not really find any recordings of albums (while surely, you have many recordings of your live sets). Is there a reason why you are not recording albums?

It is not a conscious decision that I did not record an album so far. I think I just did not put in the energy to compile enough ideas and tracks for an album and then actually record them. Usually all my preparations go into live performances. I used to record these and put them up on Soundcloud, but listening them back always gave me a feeling of flatness. It was never the same thing as it was during the live performance.

Recording an album could be good, I just don’t have practice in it. Some time ago, I asked a friend of mine: ‘hey, could you please guide me through the process of this?’, and basically, what they told me is to ‘just fucking press the Record button’ [laughs]. So yeah, I’m pretty sure I’m overthinking this whole thing. So far, I just could not get myself to do it. I feel it might have to do with my initial irritation of creating a final “solid state”, “dead” artwork… ?

The thing is, if I were to do an album, I would want it to have some strong, definitive concept. And in this case, I need to come up with a concept first. You know, it’s different with the live sets: usually what happens is that I get invited by X person to play at Y venue. So I know what the event is going to be in advance, I know who plays before and after me, so I prepare my music accordingly, the context is given. Opposed to this, when making an album, the context is not given but has to be created too.

Most of the time, when I’m working on music, I think of it not as a track, but as a performance. And by differentiating the various parts of the performance, I tend to think that those are chapters of a bigger, overarching theme.

What tools do you use for EccotVirgo?

My main instrument is my Eurorack system, I use it for synth voices, effects, and I also use a sequencer there. For modulations, I use Max. The sequencer I use is Intellijel’s Steppy, which is a really simple sequencer with four channels. Sometimes I pair that with Kompas from Bastl.

I also use the Expert Sleeper’s ES-9 module, which is a great way to integrate the Eurorack system with software, like Max or Ableton Live. This means that I can get a shitload of modulation from Max, and then I can send them to any module I want. And of course, it also has 14 analog inputs, so it also functions as a mixer and USB interface. And then, of course, in Ableton I use tools like EQs or sidechaining.

My main voice in the Eurorack system, my Chino Moreno, is the Polygogo from E-RM . It is super wide-sounding (it spreads across the frequency spectrum - ed.), and I think this is my favorite piece of gear right now. I use it everywhere I can. It can also create rhythms.

It is a rather big module, it takes up a lot of room in your Eurorack box.

Igen. It takes up a lot of space in my heart too.

Let’s talk a bit about your recent collaborations: there was UH Fest 2023 with the SHAPE residency; you performed Exoskeletal with Viola Lévai in 2021. What do you find interesting in working with other artists?

I really enjoy working with other people, and you can also learn a lot from them. I remember, for instance, I used to paint on my own a lot, but I also used to paint with others too. And when doing a collab with others on a bigger piece, then I think it has more power, unexpected turns, and I really think it’s something worth exploring.

Was this during your MOME years, this painting thing?

Well, yeah, this was during the MOME time, but actually these were graffiti walls that I was referring to.

Can you tell me a bit about the SHAPE residency with Ursula Sereghy and Orsolya Kaincz?

So, with Orsi (she’s also a modular person) and Ursula (she’s a saxophone player and electronic musician), we just started to jam in the beginning. I think Ursula and I vibed easier together because both of us were much more into… I’m not gonna say ‘dance music’ because it’s not really dance music what I’m thinking, but you know, this sort of sound; and I think Orsi is more into sound art, and she is a bit more into the academic and intellectual aspect of it. For me, the whole residency was super fun; maybe it was a bit of a struggle for Orsi to feel comfortable with something that has, for example, breakbeat in it; it took her some time to get used to it. And in the end, what we did is that we put many ideas right next to each other, one after another. It was not a big, whole composition, but rather, we were jamming, and once we felt comfortable with something we created, we said ‘great, let’s have this as chapter one’. And then we repeated this process, creating several other chapters.

When did you know that your idea for the final performance was ready?

On the day of our live set, we (with Orsi) were thinking that ‘maybe we should rehearse one last time’, but Ursula said that ‘on the day of your performance, you’re not supposed to play at all; at this point we are not getting any better, you are using up the momentum that should go to the gig, so we should just go with what we had the day before’. Up until that point, I had always wanted to be super-sure about what I played on stage, but after her words, I realized that maybe applying this mindset is a good thing.

Also, we just cannot miss your collab project HUM with Bence Barta aka. noahstas. What are your thoughts on working with Bence?

I love Bence’s work: it’s hard, dark, and fucking heavy. I think, by myself, I would not be able to go as deep or as thick with sound, but Bence easily brings out that side of me. Actually, we did some studio work, so we have some recordings. Maybe we’ll come up with an EP, or something we can show to people, so we can be invited to places (it’s not gonna work without having a release out, right?).

I really want to touch upon your current work with ONYX – I recently saw a short clip on social media, and I could not really figure out what was happening, but I saw that you as EJTECH are working on something.

So, ONYX, this Michelin-starred restaurant closed in the pandemic. Later on, in 2021, one of their spaces became Műhely, where they showed their culinary experiments, and the other one of their spaces remained empty for a long time. In the meantime, we as EJTECH took part in a group exhibition with Ludwig called Extended Present, and Ludwig asked us to create a sound space, or in other words, a sound system for ONYX, in that other, big space (The Hall of ONYX - ed.).

This is when we met the ONYX people, and after the show, they told us about their plan of reopening the place and asked us whether we would be interested in joining their team to create something unique. Of course, we said yes, as this sounded like a very cool thing to take part in.

The idea behind our work in ONYX is to create a dynamic space that is connected to all of the dishes. We created a big, soft monolith in the middle of the space, which is a dynamic textile sculpture that can change over the course of the evening. There is also a quadraphonic sound system hidden in the space, plus a bigass subwoofer. I actually found the exact resonant frequency of the space–41Hz–so when you hit that, everything starts vibrating and moving [laughs].

I’m also consulting with Ábris Gryllus on the works we are preparing for ONYX (because I love his ambient work), so while I’m composing the music, Ábris gives me pieces of advice throughout the process.

How does the composing process work? Are you working on the music in your studio and then you give ONYX the sound files, or are you actually placing Raspberry Pis or something similar with Max patches in there? Or is it a secret third thing?

The production of the big monolith happened in a place called Lumo, which is a place close to Kelenföld. All the physical work took place there, like the making of textiles and other constructions. Regarding the sound, everything is running on a Mac Mini, which is placed in a special box I designed. In that box there is also a Motu M4 USB interface and an Enntec DMX Controller. Also, regarding the user interface of the box, it has an Akai APC20 midi controller. And the whole thing runs a Max patch. It was designed in a way that I don’t have to be there in person when the dinners take place, to control the sound–what happens is that one of the waiters goes to this box, and they push one or two buttons, and then.. something happens, according to the evening’s choreography.

In this conversation, we touched upon a few key expressions, such as sound art, sound installation, and music. What’s your take on these three: is sound art different from music? Is there a different approach when one is working on one or the other?

The main approach, I think, is not on what you are creating but how you are perceiving it as a listener or spectator. When we talk about sound art, it is rather about how you dissect what is happening around you and how you intellectually digest it. The classic example is when, let's say, you arrive at a Max Neuhaus performance, and the first thing they do is that they put you on a bus that takes you outside of New York City, and then they tell you that ‘okay, now listen’. That is, pay attention to what you are listening to, and let this high-resolution soundscape happen around you.

So, sound art is utilizing sound as a material to create an experience or space, and this is what we as EJTECH are trying to do. Creating sound spaces, which are not ‘spaces that are filled with sound’, but rather ‘spaces that are created by sound’.

Music, on the other hand, is something that you do not necessarily need to understand intellectually, but rather, it’s something that moves you. This does not mean that it needs to have a rhythm or a melody, but I think music is something that is felt. Something that evokes an emotion inside of you. Sound as a material is so powerful because it affects not only the ears but your whole body too; it’s visceral.

But to give you another example: right now, we have a piece in the Budapest Light Art Museum. It’s a twelve-channel sound system, and it has a conch shell that you can interact with, so you can explore the sound. And you can see how some people approach it: they are tweaking it, trying to understand intellectually what is happening. And then, you see other people, who are just fiddling with it real fast, and then some rhythms just happen (because of the different beatings of the phases interacting with each other in a special way), and people just start vibing to it. So again, we created a tool that can either be used for sound art or to create music–it depends on just how you perceive it.

What are your plans for the future?

Well, there is the ONYX thing that’s ongoing. This year has been very hectic, to be honest, so I’d like to take some ‘studio time’ to just work on some ideas we have and develop them further.

Is there an idea or concept you wish to explore more in 2025?

Absolutely, as I mentioned earlier, I’d be super interested in somehow being able to come up with a concept I could make an album with. I hope I’ll find the time for that. With EJTECH, we will use this ‘studio time’ to further explore the already existing concepts we are working with.

Photo credit: Gabor Nemerov

This article is brought to you as part of the EM GUIDE project – an initiative dedicated to empowering independent music magazines and strengthen the underground music scene in Europe. Read more about the project at emgui.de.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Education and Culture Executive Agency (EACEA). Neither the European Union nor EACEA can be held responsible for them.